Public Health England: It’s time to tackle men’s health

Monday, July 17th, 2017 |

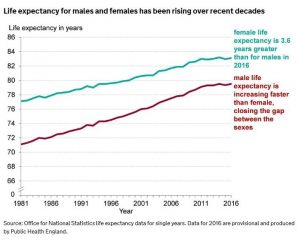

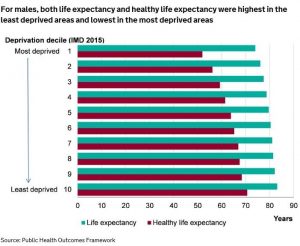

Life expectancy at birth in England remains significantly higher for females than males. In 2013-15, female life expectancy was 3.6 years higher than male life expectancy, according to new data on health inequalities published this month by Public Health England (PHE). Deprivation has a particular impact on male life expectancy: in 2013-15, men living in the most deprived areas lived 9.2 years fewer than men in the least deprived areas; the equivalent figure for women was 7.1 years.

Other key data highlighted by PHE includes:

- Healthy life expectancy at birth is higher in females than males. In 2013-15, female healthy life expectancy was 0.7 years higher than males.

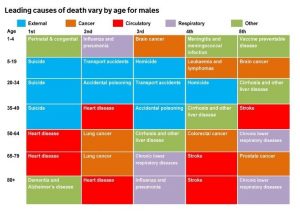

- There are large differences in premature mortality rates from cardiovascular disease between men and women. In 2012-14, there were 106.2 deaths per 100,000 population amongst males, more than double the rate of females (46.9 deaths per 100,000 population).

- Premature cancer mortality rates are much higher in men. In 2012-14, there were 157.7 deaths per 100,000 population amongst males, a statistically significant gap of 31.1 deaths per 100,000 population when compared with the rate in females (126.6 deaths per 100,000 population).

- Boys are significantly more likely than girls to be overweight or obese. At ages 4-5 in 2014/15, 22.6% of boys were overweight or obese compared with 21.2% of girls, a gap of 1.4 percentage points. More children are overweight or obese at ages 10-11 than 4-5, and there is also greater inequality between the sexes, with 34.9% of boys and 31.5% of girls with excess weight, a gap of 3.4 percentage points

- In 2014/15, the rate of alcohol-related hospital admissions was significantly higher amongst men, with 827 admissions per 100,000 population, compared with 474 per 100,000 population amongst women.

- Smoking prevalence is higher in males than in females, with 19.1% of males reporting being current smokers in 2015 compared with 14.9% of females. Smoking prevalence amongst males was higher than females across all ethnic groups; in the Asian group specifically, smoking prevalence was almost five times higher in males than females.

- The suicide rates is much higher in men. In 2012-14, there were 15.8 suicides per 100,000 population amongst males, more than three times the rate for females (4.5 deaths per 100,000 population).

- Homelessness is much more common in males with a gender split of 71% male to 29% female.

But PHE is silent about how sex and gender inequalities will be tackled. A good starting point would be the development of a national strategy for men’s health following the example of Australia, Brazil, Iran and Ireland. In Ireland, following an independent review of the country’s first national men’s health policy (2008-13), a new strategy has recently been adopted, Healthy Ireland – Men (HIM), for the period 2017-21. This aims to align men’s health policy to the government’s wider public health strategy and to maintain the momentum achieved through the original policy. PHE could begin the process by convening a multi-disciplinary symposium to consider the priority areas for action and how they can best be addressed in England.

Continued inaction on men’s health, when the evidence of the excess burden in many areas is so clear, would be tantamount to a dereliction of PHE’s duty to tackle health inequalities in all its forms.